Tackling the Burden of Osteoarthritis in Indigenous Communities

- A CALL TO ACTION -

Editorial written by OPUS PhD student Penny O’Brien

Why is osteoarthritis an important health issue?

Osteoarthritis causes pain, swelling and difficulty moving the joints. In coming years, osteoarthritis is likely to become more common as our population is becoming older and more overweight [1,2]. As people get older and heavier, the risk of developing osteoarthritis increases because the cartilage that covers healthy joints is more likely to break down. As one of the most common causes of pain and disability around the world, billions of dollars are spent each year on minimizing the health, social and economic impact of osteoarthritis [2,3]. However, until now we have rarely considered how osteoarthritis impacts Indigenous people and their communities.

What are the factors that contribute to the impact of osteoarthritis in Indigenous communities?

Indigenous communities in Australia (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander), New Zealand (Māori), Canada (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) and the United States of America (Alaskan Native and American Indian) experience high rates of obesity and smoking, along with low levels of physical activity. Because of this, there are high levels of chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease in these communities [4-6]. By the age of 35, more than half of all Indigenous people experience at least one chronic disease [6]. Lifestyle factors that are linked to these chronic conditions also place Indigenous people at a high risk of developing osteoarthritis. In Australia, Indigenous people are one-and-a-half times more likely to have osteoarthritis, when compared to the rest of the population [7]. Canadian First Nations are twice as likely to experience osteoarthritis compared to non-First nations [8]. In the United States, American Indians experience higher rates of this condition than any other group in the country [9]. Despite this, Indigenous people around the world seek care for joint pain at lower levels than non-Indigenous people. For example, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people visit general practitioners and undergo total joint replacement at half the rate expected based on the number of people living with osteoarthritis [5, 10]. Without appropriate health care, osteoarthritis can make participation in work, sport, family and cultural engagements more difficult and this can have significant impact on emotional wellbeing. Having healthy joints means that people can move more freely along a pathway to improved health and wellbeing.

Indigenous communities in Australia (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander), New Zealand (Māori), Canada (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) and the United States of America (Alaskan Native and American Indian) experience high rates of obesity and smoking, along with low levels of physical activity. Because of this, there are high levels of chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease in these communities [4-6]. By the age of 35, more than half of all Indigenous people experience at least one chronic disease [6]. Lifestyle factors that are linked to these chronic conditions also place Indigenous people at a high risk of developing osteoarthritis. In Australia, Indigenous people are one-and-a-half times more likely to have osteoarthritis, when compared to the rest of the population [7]. Canadian First Nations are twice as likely to experience osteoarthritis compared to non-First nations [8]. In the United States, American Indians experience higher rates of this condition than any other group in the country [9]. Despite this, Indigenous people around the world seek care for joint pain at lower levels than non-Indigenous people. For example, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people visit general practitioners and undergo total joint replacement at half the rate expected based on the number of people living with osteoarthritis [5, 10]. Without appropriate health care, osteoarthritis can make participation in work, sport, family and cultural engagements more difficult and this can have significant impact on emotional wellbeing. Having healthy joints means that people can move more freely along a pathway to improved health and wellbeing.

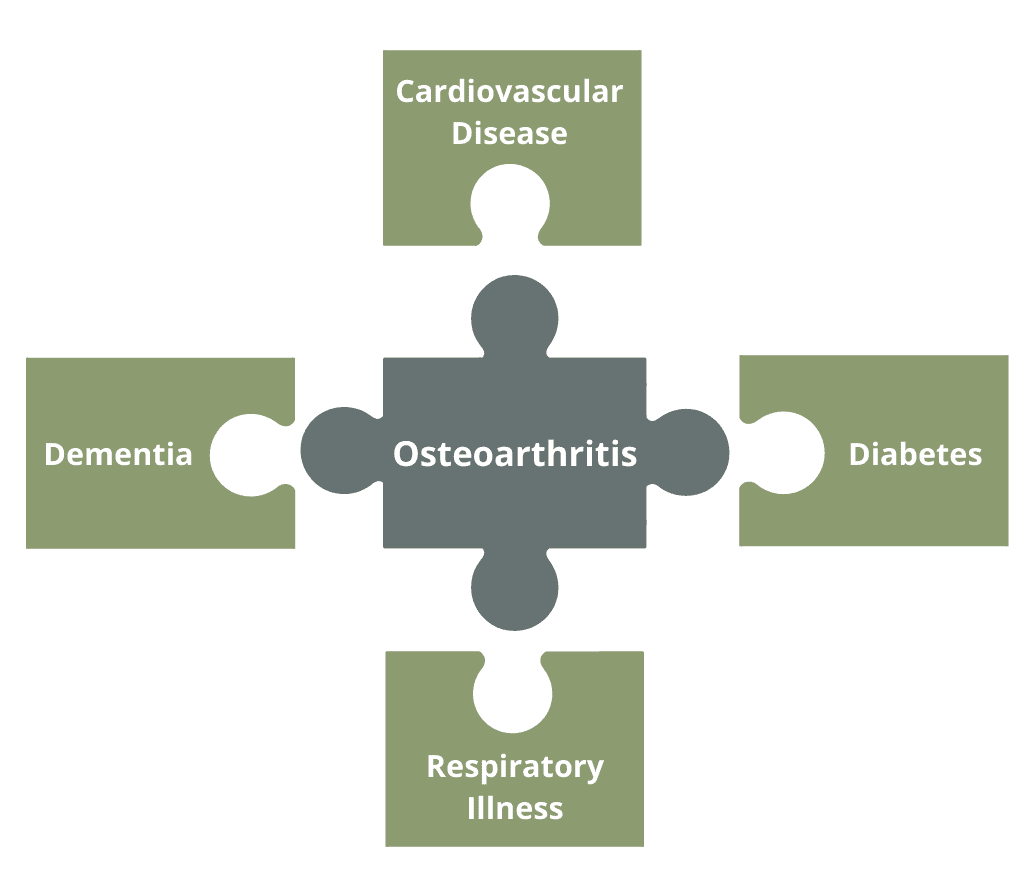

Osteoarthritis is an unmet health need for Indigenous people [11]. Until now, health care providers, researchers and policymakers have focused most of their attention on conditions that directly contribute to ‘the gap’ in life expectancy for Indigenous people. Focusing on areas such as diabetes, heart disease and childhood health is certainly important. However, as the leading cause of mobility limitation, osteoarthritis contributes indirectly to life expectancy [12]. Pain and stiffness caused by osteoarthritis can make it harder to exercise, which makes it difficult to manage other chronic conditions. Because of this, we can view osteoarthritis as a central piece of the chronic disease puzzle, which must be addressed if we are to eliminate inequalities in life expectancy. Treating osteoarthritis as a priority can help Indigenous people live longer lives, free from pain and disability.

What can we do about it?

By improving the joint health of Indigenous people, we have an opportunity to improve the wellbeing of Indigenous communities. We therefore call on health care providers, researchers and policymakers to:

- Recognise that osteoarthritis is a leading cause of pain and mobility difficulties among Indigenous people and is therefore a central piece in the chronic disease puzzle. Building capacity in the Indigenous health workforce to recognize and manage osteoarthritis must be a priority. This may be achieved by widespread education and training of the health workforce.

- Engage Indigenous people in research efforts to generate a much-needed understanding of the experience of osteoarthritis from an Indigenous perspective. More Indigenous researchers working in musculoskeletal health also means that more researchers will adopt an Indigenous view of health in their work.

- Provide culturally secure osteoarthritis care for Indigenous communities. Cultural security means that health services are committed to providing care that upholds the cultural rights, values knowledge systems and expectations of Indigenous people [13]. Embedding these principles into health care means that more Indigenous people will be able to receive the care that they need for their joint pain, so that they can remain active, healthy members of their communities.

It is now time to take musculoskeletal health off the backburner and recognise the central role that osteoarthritis and joint pain plays in managing chronic disease in Indigenous communities. We need to keep Indigenous peoples on their feet, so they can walk the path to improved health and wellbeing.

- Wittenauer, R.; Smith, L.; Aden, K. Background Paper 6.12 Osteoarthritis. Priority Medicines for Europe and the World: 2013 Update; World Health Organization Essential Medicine and Health Product Information Portal: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Hunter, D.J.; Schofield, D.; Callander, E. The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2014, 10, 437–441.

- Chen AG, Gupte C, Akhtar K, Smith P, Cobb J. The global economic cost of osteoarthritis: how the UK compares. Arthritis. 2012.

- Australian Institute of Health andWelfare. Australia’s Health 2014; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

- Brand, C.A.; Harrison, C.; Tropea, J.; Hinman, R.S.; Britt, H.; Bennell, K. Management of osteoarthritis in general practice in Australia. Arthritis Care Res. 2014, 66, 551–558.

- United Nations. State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples; United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, .

- Australian Institute of Health andWelfare. Australia’s Health 2018; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare:Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Barnabe, C.; Hemmelgarn, B.; Jones, C.A.; Peschken, C.A.; Voaklander, D.; Joseph, L.; Bernatsky, S.; Esdaile, J.M.; Marshall, D.A. Imbalance of prevalence and specialty care for osteoarthritis for first nations people in Alberta, Canada. J. Rheumatol. 2015, 42, 323–328.

- Bolen, J.; Schieb, L.; Hootman, J.M.; Helmick, C.G.; Theis, K.; Murphy, L.B.; Langmaid, G. Di_erences in the prevalence and severity of arthritis among racial/ethnic groups in the United States, National Health Interview Survey, 2002, 2003, and 2006. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2010, 7, A64.

- Dixon, T.; Urquhart, D.M.; Berry, P.; Bhatia, K.; Wang, Y.; Graves, S.; Cicuttini, F.M. Variation in rates of hip and knee joint replacement in Australia based on socio-economic status, geographical locality, birthplace and indigenous status. ANZ J. Surg. 2011, 81, 26–31.

- Lin, I.B.; Bunzli, S.; Mak, D.B.; Green, C.; Goucke, R.; Co_n, J.; O’Sullivan, P.B. Unmet needs of Aboriginal Australians with musculoskeletal pain: A mixed-method systematic review. Arthritis Care Res. 2018, 70, 1335–1347.

- Cross, M.; Smith, E.; Hoy, D.; Nolte, S.; Ackerman, I.; Fransen, M.; Bridgett, L.;Williams, S.; Guillemin, F.; Hill, C.L.; et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: Estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 1323–1330.

- Coffin, J. Rising to the challenge in Aboriginal health by creating cultural security. Aborig. Isl. Health Work J. 2007, 31, 22.